Dear Brothers and Sisters,

“The time came for Mary to be delivered. And she gave birth to her first-born son and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn” (

Lk 2:6f.).

These words touch our hearts every time we hear them. This was the moment that the angel had foretold at Nazareth: “you will bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus. He will be great, and will be called the Son of the Most High” (

Lk 1:31).

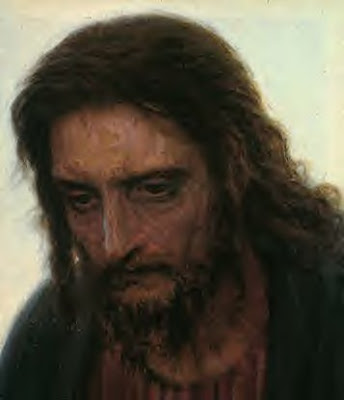

This was the moment that Israel had been awaiting for centuries, through many dark hours – the moment that all mankind was somehow awaiting, in terms as yet ill-defined: when God would take care of us, when he would step outside his concealment, when the world would be saved and God would renew all things.

We can imagine the kind of interior preparation, the kind of love with which Mary approached that hour. The brief phrase: “She wrapped him in swaddling clothes” allows us to glimpse something of the holy joy and the silent zeal of that preparation. The swaddling clothes were ready, so that the child could be given a fitting welcome. Yet there is no room at the inn. In some way, mankind is awaiting God, waiting for him to draw near.

But when the moment comes, there is no room for him. Man is so preoccupied with himself, he has such urgent need of all the space and all the time for his own things, that nothing remains for others – for his neighbour, for the poor, for God. And the richer men become, the more they fill up all the space by themselves. And the less room there is for others.

Saint John, in his Gospel, went to the heart of the matter, giving added depth to Saint Luke’s brief account of the situation in Bethlehem: “He came to his own home, and his own people received him not” (

Jn 1:11). This refers first and foremost to Bethlehem: the Son of David comes to his own city, but has to be born in a stable, because there is no room for him at the inn. Then it refers to Israel: the one who is sent comes among his own, but they do not want him. And truly, it refers to all mankind: he through whom the world was made, the primordial Creator-Word, enters into the world, but he is not listened to, he is not received.

These words refer ultimately to us, to each individual and to society as a whole. Do we have time for our neighbour who is in need of a word from us, from me, or in need of my affection? For the sufferer who is in need of help? For the fugitive or the refugee who is seeking asylum? Do we have time and space for God? Can he enter into our lives? Does he find room in us, or have we occupied all the available space in our thoughts, our actions, our lives for ourselves?

Thank God, this negative detail is not the only one, nor the last one that we find in the Gospel.

Just as in Luke we encounter the maternal love of Mary and the fidelity of Saint Joseph, the vigilance of the shepherds and their great joy, just as in Matthew we encounter the visit of the wise men, come from afar, so too John says to us: “To all who received him, he gave power to become children of God” (

Jn 1:12).

There are those who receive him, and thus, beginning with the stable, with the outside, there grows silently the new house, the new city, the new world. The message of Christmas makes us recognize the darkness of a closed world, and thereby no doubt illustrates a reality that we see daily. Yet it also tells us that God does not allow himself to be shut out. He finds a space, even if it means entering through the stable; there are people who see his light and pass it on.

Through the word of the Gospel, the angel also speaks to us, and in the sacred liturgy the light of the Redeemer enters our lives. Whether we are shepherds or “wise men” – the light and its message call us to set out, to leave the narrow circle of our desires and interests, to go out to meet the Lord and worship him. We worship him by opening the world to truth, to good, to Christ, to the service of those who are marginalized and in whom he awaits us.

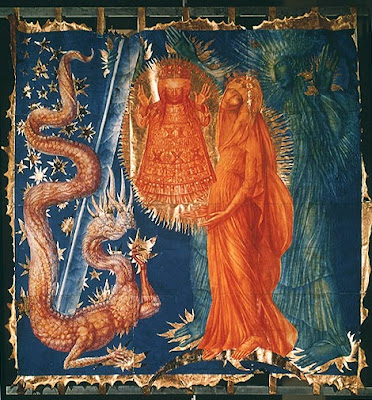

In some Christmas scenes from the late Middle Ages and the early modern period, the stable is depicted as a crumbling palace. It is still possible to recognize its former splendour, but now it has become a ruin, the walls are falling down – in fact, it has become a stable. Although it lacks any historical basis, this metaphorical interpretation nevertheless expresses something of the truth that is hidden in the mystery of Christmas. David’s throne, which had been promised to last for ever, stands empty. Others rule over the Holy Land. Joseph, the descendant of David, is a simple artisan; the palace, in fact, has become a hovel.

David himself had begun life as a shepherd. When Samuel sought him out in order to anoint him, it seemed impossible and absurd that a shepherd-boy such as he could become the bearer of the promise of Israel. In the stable of Bethlehem, the very town where it had all begun, the Davidic kingship started again in a new way – in that child wrapped in swaddling clothes and laid in a manger. The new throne from which this David will draw the world to himself is the Cross. The new throne – the Cross – corresponds to the new beginning in the stable. Yet this is exactly how the true Davidic palace, the true kingship is being built.

This new palace is so different from what people imagine a palace and royal power ought to be like. It is the community of those who allow themselves to be drawn by Christ’s love and so become one body with him, a new humanity. The power that comes from the Cross, the power of self-giving goodness – this is the true kingship. The stable becomes a palace – and setting out from this starting-point, Jesus builds the great new community, whose key-word the angels sing at the hour of his birth: “Glory to God in the highest, and peace on earth to those whom he loves” – those who place their will in his, in this way becoming men of God, new men, a new world.

Gregory of Nyssa, in his Christmas homilies, developed the same vision setting out from the Christmas message in the Gospel of John: “He pitched his tent among us” (

Jn 1:14). Gregory applies this passage about the tent to the tent of our body, which has become worn out and weak, exposed everywhere to pain and suffering. And he applies it to the whole universe, torn and disfigured by sin.

What would he say if he could see the state of the world today, through the abuse of energy and its selfish and reckless exploitation? Anselm of Canterbury, in an almost prophetic way, once described a vision of what we witness today in a polluted world whose future is at risk: “Everything was as if dead, and had lost its dignity, having been made for the service of those who praise God. The elements of the world were oppressed, they had lost their splendour because of the abuse of those who enslaved them for their idols, for whom they had not been created” (

PL 158, 955f.).

Thus, according to Gregory’s vision, the stable in the Christmas message represents the ill-treated world. What Christ rebuilds is no ordinary palace. He came to restore beauty and dignity to creation, to the universe: this is what began at Christmas and makes the angels rejoice. The Earth is restored to good order by virtue of the fact that it is opened up to God, it obtains its true light anew, and in the harmony between human will and divine will, in the unification of height and depth, it regains its beauty and dignity.

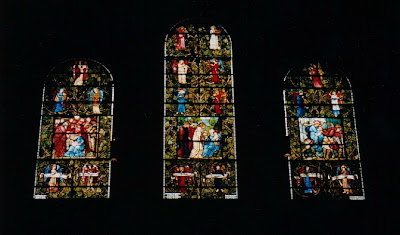

Thus Christmas is a feast of restored creation. It is in this context that the Fathers interpret the song of the angels on that holy night: it is an expression of joy over the fact that the height and the depth, Heaven and Earth, are once more united; that man is again united to God. According to the Fathers, part of the angels’ Christmas song is the fact that now angels and men can sing together and in this way the beauty of the universe is expressed in the beauty of the song of praise. Liturgical song – still according to the Fathers – possesses its own peculiar dignity through the fact that it is sung together with the celestial choirs.

It is the encounter with Jesus Christ that makes us capable of hearing the song of the angels, thus creating the real music that fades away when we lose this singing-with and hearing-with.

In the stable at Bethlehem, Heaven and Earth meet. Heaven has come down to Earth. For this reason, a light shines from the stable for all times; for this reason joy is enkindled there; for this reason song is born there.

At the end of our Christmas meditation I should like to quote a remarkable passage from Saint Augustine. Interpreting the invocation in the Lord’s Prayer: “Our Father who art in Heaven”, he asks: what is this – Heaven? And where is Heaven? Then comes a surprising response: “… who art in Heaven – that means: in the saints and in the just. Yes, the heavens are the highest bodies in the universe, but they are still bodies, which cannot exist except in a given location.

Yet if we believe that God is located in the heavens, meaning in the highest parts of the world, then the birds would be more fortunate than we, since they would live closer to God. Yet it is not written: ‘The Lord is close to those who dwell on the heights or on the mountains’, but rather: ‘the Lord is close to the brokenhearted’ (

Ps 34:18[33:19]), an expression which refers to humility. Just as the sinner is called ‘Earth’, so by contrast the just man can be called ‘Heaven’” (

Sermo in monte II 5, 17).

Heaven does not belong to the geography of space, but to the geography of the heart. And the heart of God, during the Holy Night, stooped down to the stable: the humility of God is Heaven.

And if we approach this humility, then we touch Heaven. Then the Earth too is made new. With the humility of the shepherds, let us set out, during this Holy Night, towards the Child in the stable! Let us touch God’s humility, God’s heart! Then his joy will touch us and will make the world more radiant.

Amen.

Morbelli, Angelo (Italian, 1853-1919)

Morbelli, Angelo (Italian, 1853-1919)