"The western church in the early eleventh century had emerged from almost 200 years of civil wars and invasions as a dynamic force, capable of rapid and successful expansion in adverse conditions. For since the Carolingian age Catholic Christianity had spread from its heartland in the British Isles, France, the empire, Italy and northern Spain, to become the official religion of Bohemia, Poland and Hungary and it was continuing to expand into the Viking homelands of Scandinavia and their new settlements in Iceland and Greenland.

A uniform though sparse church organisation existed throughout this huge area. All the Christian west was divided into dioceses, though they varied considerably in size; but the provision of parishes was very uneven. All towns had at least one church while some, like Rome, had more than a hundred, but even in parts of the west which had been Christian for centuries many rural areas were still served by the clergy of a central minster. The parish system was only gradually coming into being, and since over 90 per cent of the population lived in the countryside, this meant that a very high proportion of them had no regular access to a church.

Any attempt to generalise about the faith and practice of laypeople in the central middle ages is bound to be tentative. There is no statistical information available such as may later be found in parish registers, while the fairly abundant ecclesiastical legislation is often a better index of clerical expectation than of lay behaviour.

Evidence about the religious observance of individuals relates chiefly to rulers and to members of the high nobility. The practice of the rest of the population has to be reconstructed from piecing together the written and archaeological evidence about the provision of churches and clergy, the liturgical evidence about the rites which the clergy performed, the numerous charters which record the legal transactions between laymen and the church, and the anecdotal evidence found in chronicles, saints’ lives, literary works, homilies and biblical commentaries, about how laypeople were expected to practise their faith and how individuals did practise it. ...

Church membership was conferred by baptism and in ‘old’ Christian areas infant baptism was universal.

Because infant mortality was high everywhere, many baptisms must have been performed by laypeople, particularly by midwives. Everybody had the right to baptise in case of necessity, by pouring water on the candidate three times while saying in any language, ‘I baptise thee in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.’ Those who were baptised in that way might later have the additional baptismal ceremonies performed by a priest, but that was not essential.

Children who grew up in places with no parish church would have learnt about the Christian faith from their parents and from occasional visiting clergy, but their knowledge might well have been sketchy. Those who lived near a church would usually have been catechised by the parish priest and have had the chance to attend mass regularly, and the strong visual elements in the Catholic liturgy were in themselves an important means of lay instruction.

But unless they lived near a cathedral, or near a reformed monastery which encouraged lay attendance at chapel, most laypeople would never have heard a sermon, for the majority of priests were not licensed to preach. Indeed, the general level of education of the lower clergy remained poor.

There were, of course, some excellent cathedral and monastery schools which provided the best education available in western Europe, but the clergy who were trained in them did not normally undertake parish work, but were groomed for senior office in the church by being appointed cathedral canons, or chaplains in noble households.Most of the lower clergy were given a practical training in their duties by other priests, who were sometimes their fathers, and therefore their knowledge of the faith was often limited.

It is difficult to be certain how far pagan belief and practice survived in the Christian west. It persisted in some newly converted regions like Norway and Hungary, but in areas where Christianity was well established paganism seems to have merged into folklore, as may be seen, for example, in the older stories, such as Culhwch and Olwen, preserved-in the Mabinogion.

But although the imagination of people in the Christian west may have continued to have a pagan dimension, all the evidence suggests that the church had won the intellectual battle by the eleventh century, and that in general terms everybody accepted the Christian world-picture.

They believed that the universe had been created by God; that the devil had marred God’s work with man’s connivance so that evil had come into the world; that Jesus, God’s son, had by his incarnation, sacrificial death and resurrection redeemed the world; that he had founded the church to continue his work on earth; that man was immortal, and that when he died he would be judged by God and his soul would enter Paradise or be condemned to Hell; and that eternal salvation depended on accepting God’s grace in the sacraments and leading the life of Christian perfection.

Some people undoubtedly had a fuller understanding of this cosmology than others, but it provided the general framework within which everybody thought about the world in which they lived.

Lay religious practice was quite often limited. Most people knew the Lord’s Prayer and considered regular private prayer desirable. Those who lived near a church would sometimes attend mass, although only some members of the nobility appear to have done so as a matter of course on Sundays and feast days.

Most people seem to have made some effort to hear mass at the great feasts, notably Easter, but lay communion was comparatively rare in much of Europe. Marriage was not accompanied by a religious ceremony in most places.

It is impossible to tell whether laypeople went to confession at all regularly at this time. Certainly some monastic reformers urged them to do so, and the liturgical evidence suggests the tenants on some monastic estates performed penance and received absolution annually during Lent. It is known that many fighting men were reluctant to use the penitential system. They committed acts of violence in the course of their everyday lives, but the church held that serious and wilful sins of that kind could only be forgiven by making confession to a priest and performing the penance which he enjoined.

Such penances were often so lengthy, humiliating and painful that men deferred confession.

Although most people seem to have wished to make their confessions when they were dying, priests were not always available and laymen, and on occasion laywomen, sometimes acted as confessors.

In the case of those who died unshriven the church authorities normally assumed that they had repented in articulo mortis and gave them Christian burial.

A society therefore existed in the early eleventh century in which all laypeople in a general sense accepted a Christian explanation of the universe, which included personal immortality and accountability to God for their actions. But because many of them had received little instruction and had few opportunities to take part in public worship they found it difficult to live by Christian standards.

The church taught that however wicked a man had been, he would obtain eternal salvation if he wanted it, although he might have to perform harsh penances after death, but that he could be helped in this by the prayers of the church on earth. This society therefore particularly valued the reformed monasticism which had begun to develop throughout the west during the tenth century because these communities took their religious vocation of intercession for the living and the dead seriously.

There were two main types of reformed monastery: communities like Glastonbury, F´ecamp and Cluny owned extensive estates and had considerable economic and political power; the monks were noblemen and their time was spent chiefly in performing an elaborate liturgy.

The other model was the eremitical form of monasticism favoured by men like St Romuald (d. 1027), which sought to conform to the golden age asceticism of fourth-century Egypt. Such communities had few endowments, tried to avoid secular involvement, and encouraged severe fasting and corporal mortification. Their monks were recruited from a wider social spectrum than those of the great abbeys, but like them devoted their lives chiefly to liturgical prayer. ...

Reformed monasteries were regarded as centres of Christian excellence, for it was widely believed that the life of Christian perfection entailed renouncing the world, normally by taking monastic vows. This was a very natural reaction in an age when Christian standards of behaviour had only been partially accepted by society at large, which remained extremely violent. This equation of holiness with self-denial meant that the hermit monks were venerated as the Christian elite, whose renunciation of the world was on a truly heroic scale.

The outstanding example of this in the eleventh century was Peter Damian, who as cardinal bishop of Ostia was second only to the pope in the Catholic hierarchy, yet who lived as a hermit at Fonte Avellana. There were, of course, devout lay people, but in contemporary sources they are represented as seeking to behave like monks while living in the world, though it is difficult to know how accurate such descriptions are since they were almost all written by clergy. The emperor Henry II (1002–24) and Edward the Confessor (1042–66) were both credited with monastic virtues such as regular attendance at divine worship, and also the practice of chastity even though they were both married men. ...

From 1046 the papacy began to direct and coordinate the various movements for church reform. Initially the popes sought to suppress simony, the sale of church offices, and to enforce clerical celibacy, but from the reign of Gregory VII they became more ambitious and tried to secure free canonical elections of the higher clergy. This led to bitter disputes with many western rulers during the next fifty years, which were finally resolved in a number of concordats whereby, although rulers continued to control the appointment of bishops and abbots, chapters secured the right to monitor elections and to appeal to the pope against abuses.

By the twelfth century the papacy had become a dynamic power in thewestern church, but it had lost much of the fervour which had characterised the early years of reform. The reform movement had raised expectations among devout lay people which had not been entirely fulfilled, while the increase in the power of the church at all levels inevitably caused some resentment. Favourable conditions therefore existed for the growth of anti-clericalism.

During the twelfth century, except in frontier areas, most settlements of any size came to have a parish church and a resident priest. The labour involved in building churches and the cost of endowing them showed a huge degree of commitment to the church by laypeople all over the west. The existence of parish churches made the routine practice of the Christian life possible for the majority of laypeople. Although most rural priests were poorly educated and not trained to preach they were valued by their parishioners for their professional skills: they could baptise the newborn, offer the mass regularly on behalf of the parish, bless the fields at rogationtide, and, most importantly, bury the dead and pray for their souls. In some areas priests performed weddings, although in many places marriage remained a family affair. No doubt occasional church attendance became more common once every village had its own church, though there is no evidence of widespread regular Sunday attendance at mass.

But the growth of parishes also increased the possibility of conflict between clergy and laity. The cost of maintaining churches and priests was largely met from tithes, theoretically levied on all sources of income, but normally on the principal grain crops, but tithes were frequently impropriated by lay patrons, and this was a source of litigation. Another potential source of tension between the clergy and their flocks was the enforcement of marriage laws, which extended canonical impediments to the sixth degree of consanguinity, that is to people who had a common great-grandparent. It is difficult to know how rigidly or generally these laws were enforced. ...

The church hierarchy was itself affected by the changes which were taking place in the twelfth century. Thus although one of the main aims of the papal reformers had been to make a clear distinction between clergy and laity, this was to some extent neutralised by the simultaneous growth of literacy in western Europe. In the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries there was a huge increase in the number of men seeking instruction in the cathedral schools of northern Europe and the city schools of Lombardy, and since teaching was in Latin everywhere and the northern schools were controlled by the church, students came to be regarded as clergy. In northern Europe they were customarily tonsured as clerici, or clerks, and received the legal privileges of the clergy without any of the corresponding obligations. Some clerks never took major orders and were thus able to marry and live as laymen, and the distinction between clergy and laity became blurred.

Although it is sometimes argued that the increase of lay literacy contributed to the rise of heresy, this is not self-evident. Latin literacy had never been a clerical monopoly. There had always been a few lay people who could read the language: milites literati, like Baldwin I of Jerusalem (d. 1118), trained as churchmen but were recalled to the world, as well as some learned laywomen, like Adela of Blois.

Moreover, throughout much of Italy Latin was still close enough to the vernacular for lay people to have a general understanding of the liturgy. During the twelfth century the number of laymen who could understand Latin increased greatly: large numbers of civil lawyers and doctors were trained, who were good Latinists and could understand the services of the church and, if they wished, read theological works. Some merchants also could read legal Latin, and perhaps follow the liturgy, though they may not have been able to understand literary texts.

Outside Italy Latin was incomprehensible to the uneducated, but vernacular literatures were growing, and although probably very few people could read such works they nevertheless reached a wide audince. Trouv`eres were heard not simply by their patrons but by their entire households, while in towns reciters stood in the streets and entertained the general public; and the works which these men performed sometimes dealt with religious themes, like the Life of St Alexius which proved very popular.

Vernacular translations of parts of the Bible had been made earlier in monastic schools, but this process was accelerated in the twelfth century, and by the end of it substantial parts of the Scriptures had been translated into most of the main western European languages, although this was not systematic, and a complete vernacular text of the Bible was not available until almost a century later.

In the twelfth century no restriction was placed on lay access to the vernacular Scriptures, and people could own texts or listen to them being read aloud. The liturgy was not translated, but vernacular devotional books were written to help laypeople to meditate during mass. The capacity to read and write was a neutral skill, and although the spread of literacy may have aided the growth of religious dissent, it undoubtedly also led to an increase in devotional reading and a deeper understanding of the Christian faith among orthodox laypeople.

The papal reformers attempted to address the spiritual needs of important groups of lay people. They were particularly concerned about the problems of penance, which, as noted above, tended to cut fighting men off from the practice of the Christian life. The warriors were a socially amorphous group composed of the nobility and great landowners, together with armed retainers and mercenaries recruited from free peasants or serfs. The church had been concerned with the activities of these men since the mid-tenth century, when the rite for the blessing of swords for use in God’s service is first found in some German pontificals. In the early eleventh century some devout fighting men, particularly in France, responded to the church’s appeals by forming voluntary associations to limit warfare. These are collectively known as the Peace of God movement, and its supporters undertook to respect the lives and property of churchmen and the livelihood of non-combatants. ...

Most members of the western church were peasants, and attempts were also made to provide for their spiritual needs. In the late eleventh century some Benedictine houses, notably the congregation of Hirsau, had begun to profess lay brethren, or conversi and this practice was adopted by the Cistercian order in the twelfth century.

Unlike monastic servants, lay brethren took vows and lived under a rule. They did not learn Latin and participate in the choir office, but recited a simple vernacular office together at regular hours, and worked as farm labourers. This institution proved immensely popular: huge numbers of conversi were professed in the new communities, and as Southern observed, without them the Cistercians could never have undertaken their vast programme of colonising and land reclamation.

No doubt men became lay brethren for a variety of reasons, but this development must reflect the existence of a sizeable group of peasants with religious aspirations which could find no satisfaction in lay life. In the monasteries they could use their lay skills, but they were also taught how to pray, and how to grow in the life of perfection.

As these innovations show, the twelfth-century church still considered that the full Christian life entailed renunciation of the world. Such a course was not open to most people, who were married and had secular responsibilities, although it was not uncommon for people to be professed late in life after their wives or husbands had died and when their children had grown up.

Other laypeople remained in the world, but became associates of the Military Orders, and in return for benefactionswere assured of the prayers of the brethren during their lifetimes and after their deaths.

But some people no longer regarded the contemplative life as the sole Christian ideal. No doubt their attitude was shaped in part by the spirituality of the newly founded communities of Austin and Premonstratensian Canons, who had pastoral aims. Certainly some laypeople in the twelfth century were very concerned about ministering to the needs of the urban poor. For example, rich burgesses often left charitable endowments stipulating that at set times food should be provided for a fixed number of poor people and that, in accordance with Christ’s commandment, their feet should also be washed. Such benefactors were clearly aware of Christ’s teaching about the importance of good works to salvation.

Some bishops in the twelfth century tried to encourage lay piety by offering partial indulgences for a variety of activities, like going on pilgrimage, or saying certain prayers. A partial indulgence was always expressed in terms of equivalence to a period of penance (e.g. a forty days indulgence conferred the same spiritual benefits as forty days of traditional penance).

But even without these clerical stimuli, lay piety manifested itself most vigorously then as it had done for centuries, in pilgrimages. Except when they were imposed as penances, the church did not consider that pilgrimages were obligatory.

Men and women undertook these journeys voluntarily as expressions of their own religious devotion and commitment. Pilgrimage continued to be made to well-established shrines like Ste Foy of Conques and St Martin of Tours, and those of St Michael the Archangel, captain of the hosts of Heaven, and therefore popular with warriors, at Monte Gargano in Apulia and Mont St Michel in Normandy. But in the twelfth century new shrines became popular, like that of St James at Compostela, in the extreme north-west of Le´on, who was venerated as an apostle, but also as the matamoros, the patron of Christian armies in the war against Islam. In 1164 Rainald of Dassel translated the relics of the Three Kings who had come to worship the infant Christ to Cologne, where their shrine rapidly attracted large numbers of pilgrims who valued the royal magi as protectors against sorcery.

Canterbury, scene in 1170 of the martyrdom of Thomas Becket, soon became an international cult centre and a healing shrine. But although more people than ever before visited Rome on ecclesiastical business and venerated the shrines of the apostles while there, the city was no longer the chief focus of western pilgrimage as it had been before 1050; that role had passed to Jerusalem.

Pilgrimages to Jerusalem had become popular in the eleventh century particularly through Cluniac influence, but the foundation of the Crusader States made the journey quicker and safer, since it could be accomplished by sea without entering Muslim territory. Thousands of people went there each year and became familiar with the land where God’s son had lived among men.

But the Jerusalem journey continued to involve self-sacrifice: death or captivity remained genuine hazards, and the return journey from northern Europe could take almost a year if weather conditions were adverse. But people from all ranks of society went to Jerusalem, and this was a personal act of faith in which the mediation of the clergy was unnecessary. ...

The twelfth century also witnessed a great increase in devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. The liturgical observance of her principal feasts, Candlemas, the Annunciation, the Assumption and the Nativity of the Virgin, had been established in the west for centuries, but in the twelfth century her cult came to assume a uniquely exalted place in popular and ecclesiastical esteem.

The reasons for this are complex. Since the council of Ephesus in 431 the church had revered Mary as the Mother of God; but the implications of this were only fully felt on a devotional level in the western church as a greater awareness of Christ’s humanity developed there during the twelfth century. This was expressed on an intellectual level in Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo?, but was experienced by a wider public through the iconography of the suffering Christ in liturgical art and the popularity of pilgrimages to the Holy Land.

The growth in devotion to the man Christ Jesus led to an increase in reverence for his mother from whom he had received his human nature. The theological reasons for Marian devotion were set out by scholars like Anselm and Bernard of Clairvaux; but the form in which that devotion was expressed owed much to the idealisation of womanhood found in some twelfth-century vernacular poetry.

In the literature and art of the period Mary was still portrayed as the Mother of God, but she also became Our Lady, the perfect example of womanhood.

Although this perception originated in aristocratic circles, it was rapidly diffused by the iconography of the Virgin in the stained glass windows and sculptured reliefs of the new cathedrals and churches of the west.

Although there was no diminution of devotion to the other saints, Mary came to be regarded as chief intercessor, with her son, for the whole human race and worthy of greater reverence than any other of God’s creatures.

Devotion to her took many forms: some monastic communities and some secular clergy recited the Little Office of Our Lady in addition to the Divine Office. Most parish churches came to have a Lady chapel, or at least a Lady altar, and a statue or painting of the Virgin, and lay people were taught the Hail Mary in its scriptural form.

Vernacular lives of theVirginwere written and proved very popular: they drew not only on the gospels, but also on the second-century Protoevangelium, an apocryphal work attributed to the Apostle James.

The principal shrines of the Virgin were in the Holy Land, at Nazareth, Bethlehem and Jerusalem, where the church of Our Lady of Josaphat was believed to be the site of her assumption into Heaven; but during the twelfth century western models of these churches were built as devotional centres for people who could not go to the Levant, like the shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham in Norfolk. ...

Arguably the greatest change in lay piety during the twelfth century was the new way in which people came to think about Christ. The early medieval figure of divine power, the Harrower of Hell and judge of the living and the dead, was giving place to the son of Mary who had lived among men in the Holy Land and died and risen again in Jerusalem, a city familiar to thousands of western people.

In the second half of the eleventh century there seems to have been an almost total absence of religious dissent in western Europe. This period coincides, of course, with the most intense and idealistic phase of the papal reform movement and that almost certainly explains why lay people who wished to lead the life of perfection did not think it necessary to form secessionist groups, but could instead support the popes in their struggle to purify the whole church.

The Patarini of Milan exemplify this trend. They had much in common with some twelfth-century reform movements which will be considered later, and which were driven into schism through the opposition of the church authorities.

Though contemptuously named the ragpickers by their opponents, the Patarini had respectable leaders: Arialdus a scholar, Anselm a priest and the noble brothers Landulf and Erlembald. They sought to enforce the observance of the papal reform programme in their own city: they were opposed to priestly concubinage, and urged the faithful to refuse to receive the sacraments from simoniac priests. The Patarini rioted against the imperialist and unreformed Archbishop Guido in 1067 and were given the banner of St Peter by Archdeacon Hildebrand, the eminence grise in Alexander II’s pontificate. The movement lasted for a generation and spread to Piacenza and Cremona, even though its fortunes fluctuated in Milan. It received the highest accolade of papal approval in 1095 when Urban II declared that Arialdus and Erlembald might be honoured as saints."

Pages

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Christanity in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

The Sistine Chapel

Contrast also with the near contemporaneous painting of the Sistine Chapel by Léon Joseph Florentin Bonnat below

Monday, January 25, 2010

The Bishops of Ephesus and of Crete

"Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Having spoken at length on the great Apostle Paul, today let us look at his two closest collaborators: Timothy and Titus. Three Letters traditionally attributed to Paul are addressed to them, two to Timothy and one to Titus.

Timothy is a Greek name which means "one who honours God". Whereas Luke mentions him six times in the Acts, Paul in his Letters refers to him at least 17 times (and his name occurs once in the Letter to the Hebrews).

One may deduce from this that Paul held him in high esteem, even if Luke did not consider it worth telling us all about him.

Indeed, the Apostle entrusted Timothy with important missions and saw him almost as an alter ego, as is evident from his great praise of him in his Letter to the Philippians. "I have no one like him (isópsychon) who will be genuinely anxious for your welfare" (2: 20).

Timothy was born at Lystra (about 200 kilometres northwest of Tarsus) of a Jewish mother and a Gentile father (cf. Acts 16: 1).

The fact that his mother had contracted a mixed-marriage and did not have her son circumcised suggests that Timothy grew up in a family that was not strictly observant, although it was said that he was acquainted with the Scriptures from childhood (cf. II Tm 3: 15). The name of his mother, Eunice, has been handed down to us, as well as that of his grandmother, Lois (cf. II Tm 1: 5).

When Paul was passing through Lystra at the beginning of his second missionary journey, he chose Timothy to be his companion because "he was well spoken of by the brethren at Lystra and Iconium" (Acts 16: 2), but he had him circumcised "because of the Jews that were in those places" (Acts 16: 3).

Together with Paul and Silas, Timothy crossed Asia Minor as far as Troy, from where he entered Macedonia. We are informed further that at Philippi, where Paul and Silas were falsely accused of disturbing public order and thrown into prison for having exposed the exploitation of a young girl who was a soothsayer by several unscrupulous individuals (cf. Acts 16: 16-40), Timothy was spared.

When Paul was then obliged to proceed to Athens, Timothy joined him in that city and from it was sent out to the young Church of Thessalonica to obtain news about her and to strengthen her in the faith (cf. I Thes 3: 1-2). He then met up with the Apostle in Corinth, bringing him good news about the Thessalonians and working with him to evangelize that city (cf. II Cor 1: 19).

We find Timothy at Ephesus during Paul's third missionary journey. It was probably from there that the Apostle wrote to Philemon and to the Philippians; he sent both Letters jointly with Timothy (cf. Phlm 1; Phil 1: 1).

From Ephesus, Paul sent Timothy to Macedonia, together with a certain Erastus (cf. Acts 19: 22), and then also to Corinth with the mission of taking a letter to the Corinthians, in which he recommended that they welcome him warmly (cf. I Cor 4: 17; 16: 10-11).

We encounter him again as the joint sender of the Second Letter to the Corinthians, and when Paul wrote the Letter to the Romans from Corinth he added Timothy's greetings as well as the greetings of the others (cf. Rom 16: 21).

From Corinth, the disciple left for Troy on the Asian coast of the Aegean See and there awaited the Apostle who was bound for Jerusalem at the end of his third missionary journey (cf. Acts 20: 4).

From that moment in Timothy's biography, the ancient sources mention nothing further to us, except for a reference in the Letter to the Hebrews which says: "You should understand that our brother Timothy has been released, with whom I shall see you if he comes soon" (13: 23).

To conclude, we can say that the figure of Timothy stands out as a very important pastor.

According to the later Storia Ecclesiastica by Eusebius, Timothy was the first Bishop of Ephesus (cf. 3, 4). Some of his relics, brought from Constantinople, were found in Italy in 1239 in the Cathedral of Termoli in the Molise.

Then, as regards the figure of Titus, whose name is of Latin origin, we know that he was Greek by birth, that is, a pagan (cf. Gal 2: 3). Paul took Titus with him to Jerusalem for the so-called Apostolic Council, where the preaching of the Gospel to the Gentiles that freed them from the constraints of Mosaic Law was solemnly accepted.

In the Letter addressed to Titus, the Apostle praised him and described him as his "true child in a common faith" (Ti 1: 4). After Timothy's departure from Corinth, Paul sent Titus there with the task of bringing that unmanageable community to obedience.

Titus restored peace between the Church of Corinth and the Apostle, who wrote to this Church in these terms: "But God, who comforts the downcast, comforted us by the coming of Titus, and not only by his coming but also by the comfort with which he was comforted in you, as he told us of your longing, your mourning, your zeal for me.... And besides our own comfort we rejoiced still more at the joy of Titus, because his mind has been set at rest by you all" (II Cor 7: 6-7, 13).

From Corinth, Titus was again sent out by Paul - who called him "my partner and fellow worker in your service" (II Cor 8: 23) - to organize the final collections for the Christians of Jerusalem (cf. II Cor 8: 6).

Further information from the Pastoral Letters describes him as Bishop of Crete (cf. Ti 1: 5), from which, at Paul's invitation, he joined the Apostle at Nicopolis in Epirus (cf. Ti 3: 12). Later, he also went to Dalmatia (cf. II Tm 4: 10). We lack any further information on the subsequent movements of Titus or on his death.

To conclude, if we consider together the two figures of Timothy and Titus, we are aware of certain very significant facts. The most important one is that in carrying out his missions, Paul availed himself of collaborators. He certainly remains the Apostle par excellence, founder and pastor of many Churches.

Yet it clearly appears that he did not do everything on his own but relied on trustworthy people who shared in his endeavours and responsibilities.

Another observation concerns the willingness of these collaborators. The sources concerning Timothy and Titus highlight their readiness to take on various offices that also often consisted in representing Paul in circumstances far from easy. In a word, they teach us to serve the Gospel with generosity, realizing that this also entails a service to the Church herself.

Lastly, let us follow the recommendation that the Apostle Paul makes to Titus in the Letter addressed to him: "I desire you to insist on these things, so that those who have believed in God may be careful to apply themselves to good deeds; these are excellent and profitable to men" (Ti 3: 8).

Through our commitment in practice we can and must discover the truth of these words, and precisely in this Season of Advent, we too can be rich in good deeds and thus open the doors of the world to Christ, our Saviour. "

Timothy and Titus

Soon is the commemoration of the Bishops Timothy and Titus, the collaborators of St Paul.

There is a computer game (trailer above) whose central characters are Timothy and Titus.

The "blurb" reads:

"In the early days of Christianity, the faithful were being tested. The Empire, The Emperor, and pagan forces tried to obstruct and suppress the spread of the Gospel. The apostle Paul wrote letters from prison to his most trusted and beloved friends Timothy and Titus. In these letters were instructions and encouragements for starting new churches.

Now you can help Timothy and Titus retrieve Paul's letters that have been stolen by the Romans.

As Timothy and Titus seek to recover the stolen letters, their adventures lead them across the ancient lands of Crete, Ephesus and Rome to unravel the mystery of the stolen letters. They will also spread the Christian message to those they encounter along the way— from pagans and Roman soldiers, to grieving widows and angry Pharisees."

Sunday, January 24, 2010

The Conversion of St Paul

"In the first place, the conversion of Saint Paul is a greater example than the others, to prove to us that there is no sinner who may not hope for the grace which he needs...Finally, this conversion was more of a miracle than the others, since God showed by it that He could convert His cruellest persecutor, and make of him His most loyal apostle...The conversion was also miraculous in the manner in which it was accomplished, namely, the light which prepared him for conversion. This light was sudden, immeasurable, and divine...”. (De Voragine: 126)

Saturday, January 23, 2010

The Devil

"One of the problems of living in a secular society is the lack of any generalized conception of evil. The word is used often enough, notably when the headline – writers of tabloid newspapers wish to draw their readers’ attention to a particularly heinous murder. But even here, “evil” remains ill-defined, and we are in any case accustomed to having the conduct of those of our fellow citizens whom we might, in unguarded moments, describe as “evil” explained in more familiar and accessible terms by social workers and psychiatrists. Evil behaviour is the outcome of social or mental conditions rather than some abstract or personalized force.

Societies founded on a religious ethic, we might assume, would have fewer problems in developing a concept of evil. But here, too, there are difficulties. Cultures that believe in a plurality of gods have it relatively easy: some of the deities can be good, others bad, while some (and in certain cultures all) might, like human beings, combine a mixture of good and evil. But things are rather more difficult with monotheistic faiths, such as Christianity. If there is only one God, the presence of evil in the world presents a challenge: if God is presumed to be good, then evil needs explaining, as it must limit, compromise, or indeed seek to overthrow his goodness. The solution in Christianity was to create a great force for evil to oppose God’s goodness, the devil. And from the high Middle Ages (at the latest) the devil, or Satan, was a dominant figure in European Christian culture. His powers, as theologians were anxious to point out, were essentially subject to divine control; yet he acted as a constant tempter of Christians to forgo their faith, as a continual doer of evil in an uncertain and materially backward world.

Such an important cultural construct needs his historians, and P. G. Maxwell-Stuart is a very appropriate candidate for inclusion in their ranks. Maxwell-Stuart is well established as a writer on magic, witchcraft and the occult, has an in-depth knowledge of these matters over a long chronological span. One is therefore justified in turning to this volume with high expectations. But these expectations are challenged almost immediately by the “Author’s Note” at the beginning of the book. What is being offered, we are informed, is not a biography proper, but rather “a series of snapshots, each intended to give some idea of how people in succeeding Christian centuries tried to grapple with the idea of personified evil”. This, in what is a rather short book, is probably fair enough; but it does put rather a lot of weight on the choice of snapshots.

Much of the time, this choice is apposite and informative. In the early sections, Maxwell-Stuart shows how the concept of the devil developed, from the deviant courtier at the divine court of those early Middle Eastern religions from which Judaism emerged through to the rebel angel of the Old Testament and the great opponent of Christ depicted in the New Testament. Here the author uses his linguistic skills to their full advantage, analysing the uncertain and unstable terminology from which “Satan” and “the devil” were derived. There is also a very clear exposition of how ideas on the devil developed in the early Church, when even very basic theological issues, the nature of Satan among them, were uncertain and matters of debate.

The fullest treatment, however, comes in the period with which the author is most at home, the years between 1400 and 1700, when the devil’s presence was at its most marked. This was the period of the construction of the model of the satanic witch, who entered into a pact with the devil and who (in some parts of Europe, at least) attended the sabbat, that great inversion of the Catholic mass, over which Satan presided. It was also the period when instances of demonic possession proliferated, and when many Europeans were convinced that they had met the devil, or that he was adversely affecting their health, their sanity, or their social and familial relationships. By the beginning of the fifteenth century, a number of cultural, political and theological currents had coalesced to give Satan a new significance, and, as Maxwell-Stuart admirably demonstrates, Satan was to enjoy that significance until a new set of intellectual and cultural movements removed him from the attentions of most educated Europeans around 1700.

There are, however, other themes in the book which, despite being signalled, would have benefited from being developed further. The first is the role of the devil in popular culture and popular Christianity. Here, the devil was not a personification of evil in the learned theologian’s sense, but rather a trickster, tempter, general nuisance and folkvillain. Connected with this point, one feels that Maxwell-Stuart could have expanded his fascinating exposition of the ever-changing visual images of the devil that Christian art created, many of which, of course, would have been accessible to the population at large in the stained-glass windows and other decorations of their churches. "

Friday, January 22, 2010

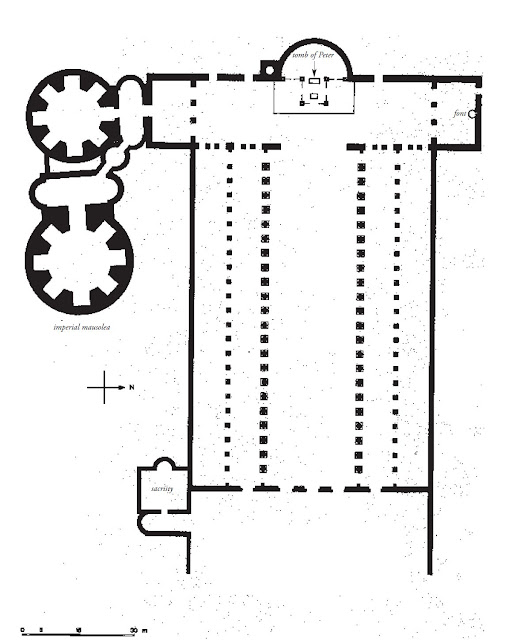

The Old St Peters

"In the nearly four centuries that had passed between the reigns of Popes Sixtus III and Paschal I, the Roman people’s perception of the great church at the Vatican had again changed radically. If in the 430s, Sixtus III had used the temporal liturgy, that is, the papal stational liturgy, to transform Constantine’s old cemetery complex into a full-fledged church in a papal system of churches, then a few generations later, in the early sixth century, Pope Symmachus exploited the rapidly growing cult of the saints, that is, the sanctoral liturgy, in a new attempt to remake St. Peter’s – to make it over into a cathedral. ...

St. Peter’s under Symmachus had already become a church with a main memorial to Peter accompanied by a number of similar, supplementary memorials to other saints. ...

[D]uring the course of the seventh and eighth century, but mostly in the eighth, the popes used a new liturgical tool, the reliquary altar, to transform St. Peter’s into a church focused on the worship of the saints, a church that had a main shrine to Peter and many secondary ones to other important saints in side chapels, and a church in which the people’s access to the sacred in all the shrines was under clerical, indeed papal, mediation."

Thursday, January 21, 2010

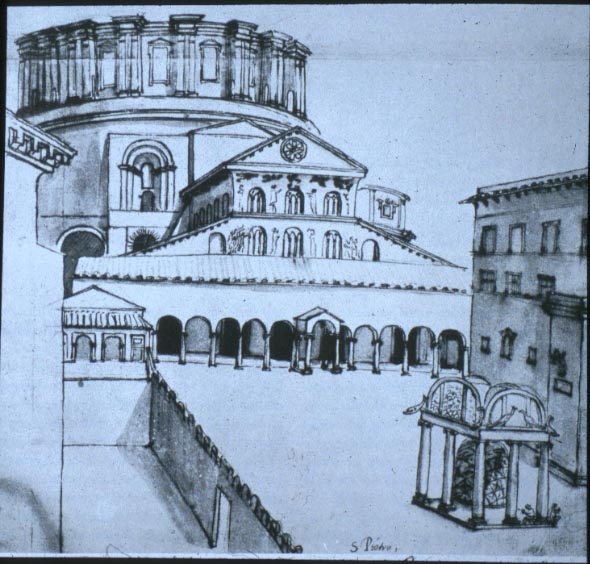

The Demolition of the Old St Peters

"At the beginning of Paul V.'s pontificate, there still stood untouched a considerable portion of the nave of the Constantinian basilica. It was separated from the new church by a wall put up by Paul III.

There likewise remained the extensive buildings situate in front of the basilica. The forecourt, flanked on the right by the house of the archpriest and on the right by the benediction loggia of three bays and the old belfry, formed an oblong square which had originally been surrounded by porticoes of Corinthian columns.

The lateral porticos, however, had had to make room for other buildings—those on the left for the oratory of the confraternity of the Blessed Sacrament built under Gregory XIII., and the house of the Cappella Giulia and the lower ministers of the church, and those on the right for the spacious palace of Innocent VIII.

In the middle of this square, at a small distance from the facade of the present basilica, stood the fountain (cantharus) erected either by Constantine or by his son Constantius, under a small dome supported by eight columns and surmounted by a colossal bronze cone which was believed to have been taken from the mausoleum of Hadrian.

From this court the eye contemplated the facade of old St. Peter's, resplendent with gold and vivid colours and completely covered with mosaics which had been restored in the sixteenth century, and crowned, in the centre, by a figure of Christ enthroned and giving His blessing.

To this image millions of devout pilgrims had gazed up during the centuries.

Internally the five-aisled basilica, with its forest of precious columns, was adorned with a wealth of altars, shrines and monuments of Popes and other ecclesiastical and secular dignitaries of every century. The roof consisted of open woodwork. The walls of the central nave, from the architrave upwards, displayed both in colour and in mosaic, scenes from Holy Scripture and the portraits of all the Popes.

It is easy to understand Paul V.'s hesitation to lay hands on a basilica so venerable by reason of the memories of a history of more than a thousand years, and endowed with so immense a wealth of sacred shrines and precious monuments.

On the other hand, the juxtaposition of two utterly heterogeneous buildings, the curious effect of which may be observed in the sketches of Marten van Heemskerk, could not be tolerated for ever. To this must be added the ruinous condition, already ascertained at the time of Nicholas V and Julius V., of the fourth century basilica a condition of which Paul V. himself speaks in some of his inscriptions as a notorious fact.

A most trustworthy contemporary, Jacopo Grimaldi, attests that the paintings on the South wall were almost unrecognizable owing to the crust of dust which stuck to them, whilst the opposite wall was leaning inwards.

Elsewhere also, even in the woodwork of the open roof, many damaged places were apparent. An earthquake could not have failed to turn the whole church into a heap of ruins.

An alarming occurrence came as a further warning to make haste. During a severe storm, in September, 1605, a huge marble block fell from a window near the altar of the Madonna della Colonna. Mass was being said at that altar at the time so that it seemed a miracle that no one was hurt.

Cardinal Pallotta, the archpriest of St. Peter's, pointed to this occurrence in the consistory of September 26th, 1605, in which he reported on the dilapidated condition of the basilica, basing himself on the reports of the experts.

As a sequel to a decision by the cardinalitial commission of September 17th, the Pope resolved to demolish the remaining part of the old basilica. At the same time he decreed that the various monuments and the relics of the Saints should be removed and preserved with the greatest care.' These injunctions were no doubt prompted by the strong opposition raised by the learned historian of the Church, Cardinal Baronius, against the demolition of a building which enshrined so many sacred and inspiring monuments of the history of the papacy. To Cardinal Pallotta was allotted the task of superintending the work of demolition.

Sestilio Mazucca, bishop of Alessano and Paolo Bizoni, both canons of St. Peter's, received pressing recommendations from Paul V. to watch over the monuments of the venerable sanctuary and to see to it that everything was accurately preserved for posterity by means of pictures and written accounts, especially the Lady Chapel of John VII., at the entrance to the basilica, which was entirely covered with mosaics, the ciborium with Veronica's handkerchief, the mosaics of Gregory XI on the facade and other ancient monuments. On the occasion of the translation of the sacred bodies and relics of Saints, protocols were to be drawn up and graves were only to be opened in presence of the clergy of the basilica. The bishop of Alessano was charged to superintend everything.

It must be regarded as a piece of particularly good fortune that in Jacopo Grimaldi (died January 7th, 1623) canon and keeper of the archives of the Chapter of St. Peter's, a man was found who thoroughly understood the past and who also possessed extensive technical knowledge. He made accurate drawings and sketches of the various monuments doomed to destruction.

The plan of the work of demolition, as drawn up in the architect's office, probably under Maderno's direction, comprised three tasks : viz. the opening of the Popes' graves and other sepulchral monuments as well as the reliquaries, and the translation of their contents ; then the demolition itself, in which every precaution was to be taken against a possible catastrophe ; thirdly, the preservation of all those objects which, out of reverence, were to be housed in the crypt—the so-called Vatican Grottos—or which were to be utilized in one way or another in the new structure.

As soon as the demolition had been decided upon, the work began.

On September 28th, Cardinal Pallotta transferred the Blessed Sacrament in solemn procession, accompanied by all the clergy of the basilica, into the new building where it was placed in the Cappella Gregoriana. Next the altar of the Apostles SS. Simon and Jude was deprived of its consecration with the ceremonies prescribed by the ritual ; the relics it had contained were translated into the new church, after which the altar was taken down. On October 11th, the tomb of Boniface VIII. was opened and on the 20th that of Boniface IV., close to the adjoining altar.

The following day witnessed the taking up of the bodies of SS. Processus and Martinianus. On October 30th, Paul V. inspected the work of demolition of the altars and ordered the erection of new ones so that the number of the seven privileged altars might be preserved.

On December 29th, 1605, the mortal remains of St. Gregory the Great were taken up with special solemnity, and on January 8th, 1606, they were translated into the Cappella Clementina. The same month also witnessed the demolition of the altar under which rested the bones of Leo IX., and that of the altar of the Holy Cross under which Paul I. had laid the body of St. Petronilla, in the year 757. Great pomp marked the translation of all these relics ; similar solemnity was observed on January 26th, at the translation of Veronica's handkerchief, the head of St. Andrew and the holy lance. These relics were temporarily kept, for greater safety, in the last room of the Chapter archives.

So many graves had now been opened in the floor that it became necessary to remove the earth to the rapidly growing rubbish heap near the Porta Angelica.

On February 8th, 1606, the dismantling of the roof began and on February 16th the great marble cross of the facade was taken down. Work proceeded with the utmost speed ; the Pope came down in person to urge the workmen to make haste. These visits convinced him of the decay of the venerable old basilica whose collapse had been predicted for the year 1609. The work proceeded with feverish rapidity—the labourers toiled even at night, by candle light.

The demolition of the walls began on March 29th ; their utter dilapidation now became apparent. The cause of this condition was subsequently ascertained ; the South wall and the columns that supported it, had been erected on the remains of Nero's race-course which were unable to bear indefinitely so heavy a weight.

In July, 1606, a committee was appointed which also included Jacopo Grimaldi. It was charged by the cardinalitial commission with the task of seeing to the preservation of the monuments of the Popes situate in the lateral aisles and in the central nave of the basilica. The grave of Innocent VIII. was opened on September 5th, after which the bones of Nicholas V., Urban VI., Innocent VII. and IX., Marcellus II. and Hadrian IV. were similarly raised and translated.

In May, 1607, the body of Leo the Great was found. Subsequently the remains of the second, third and fourth Leos were likewise found ; they were all enclosed in a magnificent marble sarcophagus. Paul V. came down on May 30th to venerate the relics of his holy predecessors

Meanwhile the discussions of the commission of Cardinals on the completion of the new building had also been concluded. They had lasted nearly two years"

[Pastor History of the Popes Volume 26 (trans Dom Ernest Graf OSB) (1937; London) pages 378-385]

It is thought that the demolition and the rebuilding of St. Peter's was responsible for the destruction of approximately half of all papal tombs up to the time of the demolition.

.jpg)

+1.jpg)

+2.jpg)