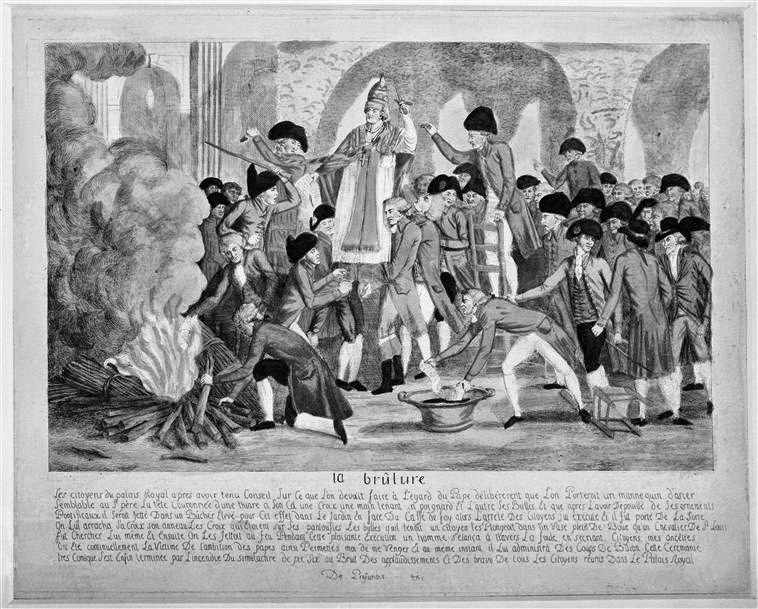

"La Brûlure" - le pape Pie VI brûlé en effigie devant le café de Foy dans les jardins du Palais Royal à Paris, le 6 avril 1791

Engraving

42.5 x 54.5 cm

Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles

.Le Traité de paix avec Rome : baisez ça papa et faite pate de velours

The French government`s view of the Treaty of Tolentino

1797

Engraving

23,5 x 30 cm

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Giuseppe Pietro Bagetti (1764 - 1831)

Entrée à Rome des troupes françaises commandées par le Général Berthier, le 11 février 1798

Aquarelle

80 x 118 cm

Musées de l'île d'Aix, Île d'Aix

Hippolyte Lecomte (1781-1857)

Entrée de l'armée française à Rome: Le général Berthier est à la tête de l'armée, 15 février 1798

1834

Oil on canvas

77 x 99 cm

Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles

Entrée triomphante des Français dans Rome

Print

Musée de l'Armée, Paris

Jean Duplessi-Bertaux (1747 - 1819) and Robert Delaunay (1749 - 1814)

The proclamation of the Roman Republic in Piazza del Campidoglio

1798

31 x 42,5 cm

Département Estampes et photographie, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

After: Giacomo Beys (1801 - 1804; fl.)

Print made by: Giovanni Petrini (1800 - 1812; fl)

Ordine del Direttorio Esecutivo di parigi presentato a S.S.Pio VI

The Order of the Directory in Paris commanding the Pope to leave Rome

1801

Engraving

398 millimetres x 487 millimetres

The British Museum, London

After: Giacomo Beys (1801 - 1804; fl.)

Print made by: Alessandro Mochetti (1760 - 1812)

Partenza da Roma di S.S.Pio VI

Pope Pius VI embarking in coach-and-four, escorted by French dragoons

1801

Engraving

378 millimetres x 477 millimetres

The British Museum, London

Planting of the Tree of Liberty on the Capitol, Rome

Felice Giani (1758-1823)

Altare patrio a piazza San Pietro per la Festa della Federazione

1798

Oil on panel

38 x 53 cm

Museo di Roma, Rome

The Altar in St Peter`s Square, Rome on the Festa della Federazione 1798

Felice Giani (1758-1823)

Arco trionfale eretto a ponte Sant’Angelo per la Festa della Federazione

1798

Oil on panel

38 x 53 cm

Museo di Roma, Rome

Anonymous

Départ de Rome du Troisième convoi des statues et monumens des arts

1798.

Engraving,

Source: Volume 140, number 12336,

Collection de Hennin, Salle des Estampes, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

Benjamin Zix 1772 - 1811

Arrivée au Louvre des trésors d'art de la Grande Armée

Drawing: brown ink, brown wash, pencil

25.3 x 44.6 cm

Musée du Louvre, Paris

On the French Revolution Pius VI had first adopted a silent attitude

However as events unfolded he was compelled to issue his Brief Aliquantum condemning events and the undermining of the Church

Such opposition did not go unnoticed and led to the burning of the effigy of the Pope at Versailles and other more violent measures against the Church and the Papacy

The Pope rejected the "Constitution civile du clergé" on 13 March, 1791, suspended the priests that accepted it, provided as well as he could for the banished clergy and protested against the execution of Louis XVI.

The Papal States were attacked and taken over leading to the Papal humiliation of the Treaty of Tolentino

Then matters went further:

"On January 11th, 1798, a definite order was issued by the French Government to its troops to march on Rome and occupy it.

The army accordingly moved southwards, under General Berthier, with orders from Bonaparte to expel the Pope and set up a republic in Rome. The Cardinals besought the Pope to take refuge in Naples, but this he refused to do and remained steadfastly at this post, prepared to endure whatever the future might have in store for him.

On February 9th the French occupied Monte Mario and the Ponte Molle, and Berthier received visits from Azara [the Spanish ambassador to the Vatican] Duke Braschi, Doria, the Secretary of State, and other high-ranking diplomats. The next day Berthier made known his terms of capitulation. The demands made for the atonement of the " attack " of December 28th [on the alleged attack on the French ambassador who had subsequently died] far exceeded all previous ones, so far as payments of money and cession of territory were concerned, and they included the production of four Cardinals and four nobles as hostages and the imprisonment of high prelates and dignitaries.

Naturally the special confidence of the French general was enjoyed by Azara, with whom he discussed all the details of the action he intended to take in the next few days ; his desire, he told him, was to occupy Rome without resistance and without bloodshed.

In a report rendered at this time Azara proudly relates how he prevailed on Berthier to allow the religious life of the city to continue without the slightest interruption, religious services to be held as before, as though there were no Frenchmen there at all, and the Pope to exercise his priestly functions with complete freedom and to retain his guards and palaces, his soldiers, and his police. He had been able to obtain these favours from Berthier without any great difficulty, as no one could be more humane than he.

The College of Cardinals decided to comply with Berthier's conditions.

On February 10th the surrender of Rome to the French revolutionary army was signed and executed. An edict issued by the Secretary of State had already threatened with the death penalty anyone who molested the French.

Everything possible was done to maintain public order. Azara, who now acknowledged that he was a friend of the French, exhorted the Spaniards in Rome to behave sensibly.In his reports to Madrid he was full of praise for Berthier's behaviour and referred sarcastically to the lethargy and pious helplessness of the Romans.

Presumably Berthier purposely chose February 15th, the anniversary of the Pope's election, as the day on which to carry out the revolution, in accordance with his orders. Hitherto he had not said a single word about it.

After the ecclesiastical celebration of the anniversary the seven Cardinals who had taken part in it were kept under surveillance by a French officer in the Secretary of State's apartments, while the French troops entered the city, joined up with the revolutionary conspirators, and in the presence of a vast crowd erected a tree of liberty on the Capitol.

Here a document was read, announcing the deposition of the Pope as a temporal sovereign and the erection of a Roman republic.

In the afternoon Berthier, with a military escort, made his entry into the city, where he was received by the people in silence.

On the Capitol he made a speech in which he recognized, in the name of the French Republic, the new political order.

Pius VI., who was again suffering from his physical ailments, received the first report of these events with calmness and composure. In the evening he was officially informed by the commandant of the city. General Cervoni, that the Roman people, disgusted with the abuse of political power, had decided to regain possession of its sovereignty and its freedom and had set up a government of its own.

As the protectress of the freedom of all peoples, the French nation had not been able to oppose this urgent desire. The Pope's person was inviolable and he could continue to exercise his spiritual functions as the first Bishop of the Church. To these fine words Pius VI. replied that he respected the inscrutable designs of divine Providence.

Thereupon the Quirinal and Vatican were occupied, the archives and offices were taken over, and the Pope was declared to be in protective custody.

Azara's report of February 16th speaks in solemn words of the " epoch in world history " initiated by the destruction of the temporal power of the Pope and the resurrection of the Roman republic. Azara had not been entirely free of responsibility for these events, but even he began to feel a little uneasy when the revolutionaries planted a tree of liberty outside his windows and proclaimed that they were fighting not only against the Pope but against all sovereigns....

But the Pope had yet to undergo the heaviest blow expulsion from the Vatican and the Eternal City. On February 17th he was informed that he would have to leave Rome within three days. Azara relates how the commissary Haller put troops into the Papal palace and then presented himself to the Pope, whom he informed that he could go to Tuscany. Provision would be made for the journey and his maintenance.

The Pope rephed with astonishing composure that they could do what they liked with him, but he would neither leave Rome nor desert his Church. It was not till Haller and Cervoni threatened to use force that he gave way. His wish to be allowed to choose Naples as his place of exile had been refused.

Although he was seriously ill he discussed his departure with Cardinals Doria, Gerdil, and Antonelli. He imparted all necessary powers to the members of the Sacred College who were staying behind, and at Antonelli's suggestion he nominated a special Congregation under the latter's presidency, consisting of two members of each of the three cardinalitial ranks.

It was February 20th, 1798. Long before daybreak Pius VI. heard Mass and afterwards enclosed the Blessed Sacrament in a small case which he hung round his neck.

Eighty years old, frail, and mortally sick, he entered the travelling carriage that awaited him in the Cortile di San Damaso. He was accompanied by two clerics, the Maestro di Camera Caracciolo and the ex-Jesuit Marotti, and his physician Tassi.

An hour before sunrise the party left Rome unnoticed, attended only by some French officers in another carriage. Tears came to his eyes as he saluted for the last time the church of St. Peter and the tomb of the Prince of the Apostles. It was exactly a year and a day since the conclusion of the peace of Tolentino, which he had hoped in vain would spare his beloved Rome the worst indignity. Now he was to leave St. Peter's city as an exile, under cover of darkness, and leave it for ever.

Siena was reached in five daily stages, and here he was at first accommodated in the convent of the Hermits of St. Augustine ...

In consonance with the talk in Paris of freeing the descendants of Brutus from the tyranny of fanaticism, Berthier's speech on the Capitol was full of turgid reminiscences of ancient times :

" Manes of Cato, Brutus, and Cicero, accept the homage of free Frenchmen on the Capitol, where you so often defended the rights of the people and celebrated the Roman Repubhc ! These sons of the Gauls, with the olive branch of peace in their hands, will re-erect on this hallowed spot the altars of freedom that were set up of old by the first Brutus" ...As in every revolution, these phrases were followed by a reality that in many respects was well up to the standard of the Reign of Terror. The new government was based on military force.

All suspicious persons were condemned to death and any French emigres who had not already escaped were expelled.

Day after day a fresh crop of ordinances and announcements was issued by the new Government.

For the maintenance of public order a National Guard was formed.

The mob flocked to the great popular festivals in the Piazza di S. Pietro, where it listened with enthusiasm to high-flown speeches about the golden age that had just begun. A month later there was a huge festival of brotherhood in the piazza, attended by representatives of every district of the new republic.

But quite a time was to pass before the people was allowed to govern itself. The new constitution had little of the antique about it ; it was modelled rather on the French pattern of the year III. The only indication of the promised revival of ancient Rome was some unimportant modifications, the most notable of which were some badly chosen official titles.

Thus, at the head of the new State were five consuls, and the legislative power was vested in two chambers, the Tribunal, with seventy-two members over twenty-five years of age, and the Senate, with thirty-two members over thirty-five years.^Paying no attention to democracy, General Massena, the successor of Berthier, who was recalled to Paris, appointed the consuls and most of the representatives of the people according to his own judgment. Further, for the time being at least, the French generalissimo, who received direct instructions from Paris, was to control the consuls. ....The French troops, not having received any pay for a long time, failed to live up to their role of popular benefactors and soon deteriorated into plunderers. The French showed themselves to be adept at systematically robbing Rome of its unique wealth of art treasures accumulated in the course of 2,000 years.

Paris, the capital of the great Republic, was to be the artistic as well as the political centre of the West ; Rome, therefore, had to surrender the treasures assembled there by emperors. Popes, and aristocrats.

The delivery of works of art and manuscripts had been demanded by Bonaparte at Bologna and Tolentino. The cities of northern Italy had already been despoiled. Correggio's works were moved to France from Parma ; Modena, Ferrara,and Verona had to make their contributions ; the works in silver from the churches in Milan were partly melted down, partly transferred to Paris ; Bologna lost over 500 valuable manuscripts, and in Venice hands were laid on the treasury of St. Mark's.

And now it was the turn of Rome.

In March-July 1798, the plundering was carried on with feverish activity. On one day alone a long procession of 500 horse-drawn vehicles, under a strong military guard, was seen leaving the city. It contained an immense number of antique sculptures and Renaissance paintings that France was appropriating in accordance with the peace of Tolentino.

They included the Laocoon group, the Belvedere Apollo, the Dying Gaul, Cupid and Psyche, Ariadne on Naxos, the Medici Venus, and the colossal figures of the Tiber and the Nile ; tapestries and paintings by Raphael, including the Transfiguration, the Madonna di Foligno, and the Madonna della Sedia ; Titian's Santa Conversazione ; and many other works.

It was not till several years after that these stolen treasures were exhibited in the Musee Napoleonien in the Louvre, which was opened in 1807. After Napoleon's downfall most of these works, together with other trophies of his, were returned to their former places.The losses in precious metals and stones were equally extensive ; everything that could be carried was taken by the French to their own country. All the churches and palaces were stripped.

On one day, under the direction of the Papal Captain Crispoldi, gold and silver bars to the value of 15,000,000 scudi were taken away in coffers. They had been abstracted from the Castel S. Angelo, the Monte, and the properties of the Cardinals and patricians. At the beginning of April pearls and precious stones valued at 4,000,000 scudi were taken off to France ; they included 386 diamonds, 333 emeralds, 692 rubies, 208 sapphires, and many other stones.

Most of them came from the famous tiaras of Popes Julius II., Paul III., Clement VIIL, and Urban VIII.

On July 8th 500 of the most valuable manuscripts were surrendered, at the loss of which Cardinal Borgia and Monsignori Marini and Caracciolo were said to have wept like children.

A week later a vast herd of 1,600 horses trotted out of Rome, destined for the French army in Italy.

The Romans watched with silent grief the removal of the treasures that had been so proudly preserved, the wanton damage done in the gardens and collections of the Vatican and the great private libraries, the sale by auction at pitifully low prices of the treasures belonging to the Pope, the Cardinals, the Villa Albani, the Farnesina, and other houses ..

It was even proposed to blow up the Castel S. Angelo, carry off the obelisks, and remove Raphael's frescoes from the Stanze.

This vandalism on the part of a civilized nation is unique in history and is one of the blackest crimes committed by the French Republic. This colossal robbery, combined with the economic and financial oppression of the Roman people, which became more and more intolerable, aroused the greatest popular indignation, resulting in several outbreaks that had to be quelled by force of arms.

To support and superintend the steps taken by General Massena, the Directory set up a military commission of four members in Rome, and Massena became nothing more than an executive instrument. The exploitation of the people, however, went on worse than ever.

After a time Massena was disliked by his own troops, and the commissioners had to devise means of checking a threatened mutiny. When both officers and soldiers refused to obey him Massena fled from Rome, and the commissioners, having declared that they would have nothing more to do with him received fresh and more extensive powers from Paris.

It soon became apparent that with the surrender of Rome insupportable obligations had been laid on a State which had already been severely weakened by the treaties of Bologna and Tolentino.

Both private and public resources were exhausted and plundered to such an extent that even the commissioners reported on the financial incapacity of the Roman State. The paper money, which had long been the sole form of currency, was apparently about to share the fate of the French assignats.

Domestic life was ruined, financially and otherwise, by the incessant quartering.

Religious houses were converted into barracks and subjected to exorbitant taxes, and 200 of them were dissolved.

For strangers, too, residence in Rome was anything but pleasant. Everyone, including the Auditors of the Rota and the Generals of religious orders, had to furnish the Government with personal particulars. The diplomatic representatives began to feel unsafe. Fuming with indignation at the continual infractions of international law, Azara, in March 1798, decided to leave Rome and retire to Florence. Almost as soon as he arrived there he was offered the post of Spanish ambassador in Paris, which he accepted. While occupying this position, too, he remained a lifelong supporter of "Enlightenment"."

From Chapter VIII, Bonaparte and the French in the Papal States: The Establishment of the Roman Republic and the Expulsion of the Pope. in Ludwig Pastor, The history of the popes from the close of the Middle Ages : drawn from the secret archives of the Vatican and other original sources Volume XL (1899) (trans E F Peeler 1953)

In his book A brief account of the subversion of the papal government. 1798. (London, J. Murray; [etc.etc.] 1807. 3d. ed.) the young English artist Richard Duppa (1770-1831) described the scene in St Peter`s Square on 20th March 1798:

"That the regenerated Roman people might be constitutionally confirmed in their newly-acquired rights, a day was set apart solemnly to renounce their old Government, and swear fidelity to the new. For the celebration of this solemnity, which took place on the 20th of March, an Altar was erected, in the middle of the piazza of S. Peter's, with three statues upon it, representing the French, Cisalpine, and Roman Republics.

Behind the Altar was a large tent, covered and decorated with silk of the Roman colours, surmounted with a red cap, to receive the deputies from the departments.

Before the Altar was placed an open orchestra, filled with the same band that had before been employed to celebrate the funeral honours of Duphot.

At the foot of the bridge of S. Angelo, in the piazza di Ponte, was erected a triumphal arch, on the general design of that of Cons tantine in the Campo Vacino, on the top of which were placed three colossal figures representing the three Republics. As a substitute for bass reliefs, it was painted in compartments in chiaroscuro, representing Buonaparte's most distinguished victories in Italy. Before this arch was another orchestra.

The ceremony in the piazza began by the marching in of the Roman legion, which was drawn up close to the colonnade, forming a semicircular line; then came the French infantry and cavalry, one regiment after another alternately, drawn up in separate detachments round the piazza.

When all was thus in order, the Consuls, on foot, made their entrance from the Vatican palace, where they had robed themselves, preceded by a company of national troops and a band of music; and, if the weather had permitted, a number of citizens, selected, and dressed in gala, for the occasion, from the age of five years to fifty, were to have walked two and two, carrying olive branches; but an excessively heavy rain prevented this part of the procession.

Before the High Altar, on which the statues were placed, there was another smaller one with fire upon it. Over this fire the Consuls stretched out their hands, swore eternal hatred to monarchies, and eternal fidelity to the Republic; and then one of them committed to the flames a scroll of paper containing a representation of all the insignia of royalty, as a Crown, a Sceptre, a Tiara, &c. after which the French troops fired a feu-de-joie, and at a signal given, the Roman Legion raised their hats in the air upon the points of their bayonets, as a demonstration of attachment to the new Government: but there was no shouting—no voluntary sign of applause; never on any public occasion in which the people were intended to act so principal a part, was a more decided disapprobation tacitly shewn.

After the Fete was concluded, the French officers, with the Consuls and Deputies from the departments, dined together in the papal palace on Monte Cavallo, and in the evening they gave a magnificent ball to the ex-nobles and others their partizans, which was numerously attended; with the exception of the houses Borghese, Santacroce, Altemp, and Cesarini, no distinguished family, from desire or inclination, was present; but it was now no longer time to accumulate additional causes for oppression, and he who hoped to save a remnant of his property, avoided giving occasion for personal resentment.

At night the dome of S. Peter's was illuminated, with the same splendor as was customary on the anniversary of S. Peter's day. This was the second time of its illumination since the arrival of the French: it was before displayed on the evening of the solemn Fete to honour the manes of Duphot, which was done to gratify the officers that were to leave Rome on the morrow.

The day after this Federation, the French published the Roman constitution in form, which was only a counterpart of the one given to the unfortunate Venetians, consisting of three hundred and seventy-two articles, and which it would be unnecessary to transcribe, as it contained only the common-place professions given by the French on all similar occasions."

No comments:

Post a Comment